Community Centered Evidence-Based Practice Approach

As a field, we must reimagine evidence-based practice and develop inclusive program implementation and evaluation methods that are equitable and community driven in addition to data informed.

As a field, we must reimagine evidence-based practice (EBP) and develop inclusive program implementation and evaluation methods that are equitable and community driven in addition to data informed. According to Kayla Tawa’s 2020 report, Redefining Evidence-Based Practices: Expanding our View of Evidence, “despite the shortcomings of Evidence Based Practices, policymakers often make decision about resources based on evidence, with EBP being the gold standard. When that happens, EBPs can cause harm.”

In an effort to improve our effectiveness alongside pressure from funders, many social justice fields have become solely focused on implementing and replicating evidence-based practices. While EBPs have a role in program development and practice, many EBPs have been created for and tested with a single population and privilege certain types of knowledge. As a result, many EBP’s lack cultural, contextual, and community relevance. These models and approaches are often created and evaluated within mainstream, white, Western cultural norms, and often focus on problems, not people. Furthermore, many domestic violence interventions focus on either adult survivors or child survivors and fail to recognize the inextricable link between parents and children and the effectiveness of multi-generational approaches. Disconnects such as these contribute to the perpetuation of structural inequities and reinforce a Western medical model of the treatment of symptoms, rather than creating the experiences and conditions that support healing and conditions for families to thrive. In the US, dominant culture narratives (e.g. White, heterosexual and/or colonial racist narratives) have historically shaped the ways that evaluation is conceptualized, data is collected, analyzed and interpreted. When we fully recognize lived expertise as evidence and account for community and cultural context, we can elevate innovative programs that were developed by and for the communities they serve. This kind of approach could lead to reducing structural inequities and improve outcomes for those most impacted by family violence.

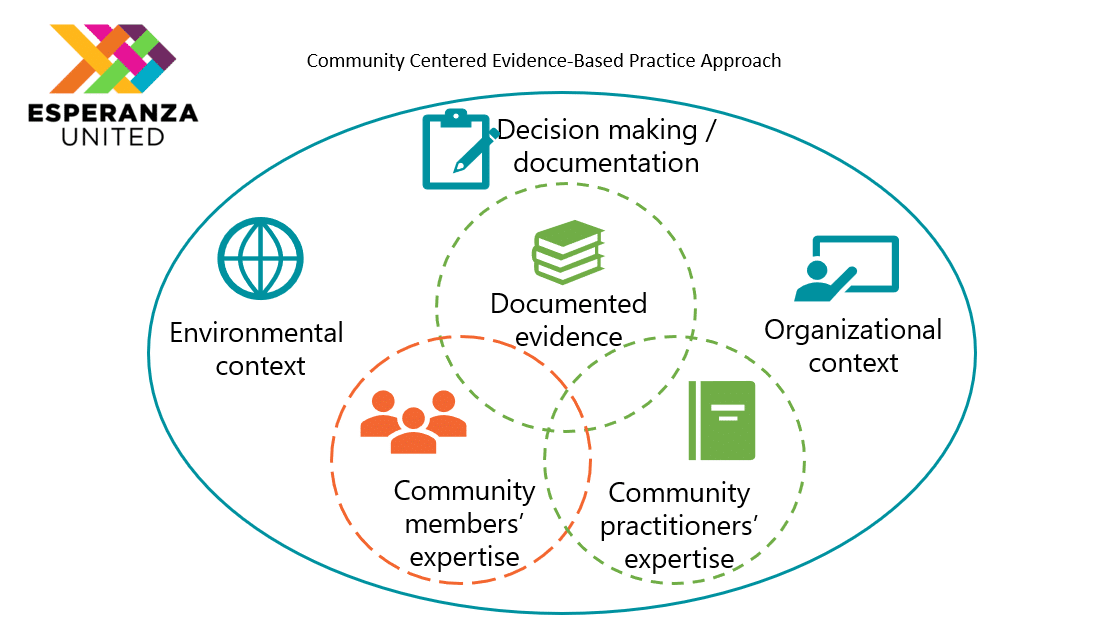

As demonstrated in the graphic above, despite the long-standing history of culturally specific work being critical to meeting the needs of families, there has been a limited investment in documenting and developing the evidence-based for culturally specific services. Given the challenges inherent in generalizing evidence based practice approaches to a wide range of services, Esperanza United and other culturally specific resource centers have facilitated discussions on community-relevant approaches to evidence-based practice.

After consultation with the research literature, a national workgroup of researchers, community practitioners and ongoing feedback from national audiences, Esperanza United adapted the Transdisciplinary model (Satterfield et al., 2009) to reflect their unique perspective. The result of this work has been captured in the following Community Centered Evidence-based Practice Approach and is intended to bridge culturally relevant, community based scholarship and EBP for the field of DV. The model centers community expertise as a key component of EBP. Community expertise enhances the culturally and contextual relevancy of programming. It requires practitioners and evaluators to actively collaborate with the communities they serve on practice and implementation, as well as decision making and documentation efforts.

It is important to note that while the Community Center Evidence Based Practice Approach centers community expertise, it still retains other forms of evidence to guide decision making in EBP. This evidence includes traditional documented evidence (e.g. research studies and formal evaluations) and the expertise of community practitioners (e.g. advocates, childcare workers, etc.). Community practitioners, such as those on the front-line, can share valuable information on what may or may not work when weighing decisions about EBPs and program evaluation. Collectively these three areas of evidence can lead to more effective programming and begin to bridge the gap between “what works” and “for whom.”

For more information on this approach visit Esperanza United’s Building Evidence Toolkit

We must continue to push the field, funders, and policy makers to redefine Evidence Based Practice as both data driven AND grounded in community and survivor voice. To do this successfully, domestic violence and child serving organizations should move beyond one size fits all interventions and instead create strategies and interventions that are based on individual, family, and community contexts. “Until we recognize lived experience and other nonexperimental data as evidence, promising programs will continue to be under resourced, perpetuating inequity,” (Tawa, 2020).